Like the relationship between dogs and young children, that between cats and kids has much to offer—provided the child’s parents or caregivers recognize the needs and limits of cat and child alike. Unfortunately, many times parents know little or nothing about normal feline behavior, and what little they do know comes from poorly informed media sources. Other times they may mistakenly perceive cats as little dogs. Both behaviorally and physiologically, the latter approach wouldn’t work even if the underlying canine knowledge were sound. But as we saw in the previous two commentaries, often people’s knowledge about dogs is pretty iffy, too. In that case, we wind up with misinformation regarding one species being inappropriately applied to members of another. When it comes to cats and kids, the net result of this is that someone could get hurt.

Like the relationship between dogs and young children, that between cats and kids has much to offer—provided the child’s parents or caregivers recognize the needs and limits of cat and child alike. Unfortunately, many times parents know little or nothing about normal feline behavior, and what little they do know comes from poorly informed media sources. Other times they may mistakenly perceive cats as little dogs. Both behaviorally and physiologically, the latter approach wouldn’t work even if the underlying canine knowledge were sound. But as we saw in the previous two commentaries, often people’s knowledge about dogs is pretty iffy, too. In that case, we wind up with misinformation regarding one species being inappropriately applied to members of another. When it comes to cats and kids, the net result of this is that someone could get hurt.

The good news about cats is that their more solitary nature leads many to view infants and young children as offspring rather than engage in competitive relationships with them. If the cat has the confidence to handle this, he or she may become a self-appointed mom’s or dad’s little helper, carefully observing the baby’s nursing/feeding, bathing, and diaper-changing rituals to ensure it’s done properly. These cats also may periodically check on the sleeping infant just like any concerned parent.

Some cats who adopt this approach will even attempt to teach the child to hunt, a routine that’s not uncommon when a new puppy is added to a household that already includes a hunting cat, and especially a female. A friend tells the story of how he and his wife brought home their first newborn and lovingly placed her in her brand new crib in their perfectly decorated nursery. After making sure she was sleeping, they slipped away to the kitchen to get something to eat. When they returned, they found a dead mouse carefully positioned beside the sleeping infant and the cat curled up sound asleep at the opposite end of the crib.

Fortunately both parents knew enough about feline behavior that they were not so horrified by this feline act that they immediately carted the cat off to the veterinarian’s to be euthanized for disgusting or dangerous behavior. Instead, they saw the behavior for what it was: the cat’s attempt to feed her young. As my friend noted when he recounted the tale to me later, “Who knows? Maybe the cat was appalled that we went off and fed ourselves and left the baby there alone and with nothing to eat.”

There are many such stories of feline devotion and I’ve had similar experiences with my own cats and kids as infants, the memories of which I cherish. However, it would be naive to believe that all cats are like this. Similarly, it would be as misguided to believe there was something wrong with a cat who chose to have minimal contact with an infant or child as it would be to believe likewise about one of those furry nannies.

The not-so-good news about cats for some parents is that cats are, at heart, cats. And that means that they are members of a nonverbal species that communicates with their teeth and claws. Like dogs, how much force they put behind their jaws depends on how much stimulation they get from their targets or the environment. When a queen (mother cat) picks up her kitten by the scruff of the neck, the kitten instinctively knows to remain silent with limbs curled close to the body. Not only does this make it easier for the queen to transport her young, it prevents predators from being alerted by any kittenish thrashing or noises during this vulnerable period. While the queen does hold her kittens with her teeth, they’re unharmed because she applies just enough pressure to get the job done.

When the job the adult cat wants done is offing a rodent or confronting a predator, that’s a whole different ball game. In that case, the stimulus the cat receives from the other triggers a far more powerful bite. Similarly, gentle playful and disciplinary batting with paws can give way to slashes with unsheathed claws when stimulus reaches a certain level.

Theoretically, the solution to this potential problem is simple: don’t stimulate the cat in a manner that increases the likelihood that the animal will bite or unsheath those claws. However, that’s one of those things that’s often a lot easier to say than actually do for two reasons.

The first is that young children can be both noisy and unpredictable. Unless adults have taught the child to be quiet, gentle, and respectful around animals, the potential exists for a cat who merely intended to hold the little poking and prodding child’s finger to clamp on if the child squeals in surprise or even delight. If parents or other caregivers panic and rush or yell at the cat, that could produce the same unfortunate result. If those folks roughly grab the cat and yank the animal away from the child, they shouldn’t be surprise if the cat’s claws come out and dig in at the same time as those fangs dig in deeper, turning that small puncture wound into a deep laceration.

Sadly, when this occurs people lacking knowledge of normal feline behavior blame the cat for what they consider an abnormal response. Those with knowledge of normal feline behavior don’t do this, primarily because they don’t put their kids and their cats in this position.

Sadly, when this occurs people lacking knowledge of normal feline behavior blame the cat for what they consider an abnormal response. Those with knowledge of normal feline behavior don’t do this, primarily because they don’t put their kids and their cats in this position.

What about infants who may spend a fair amount of their waking hours crying and flailing about? With rare exceptions, cats seem to recognize that infants pose little threat compared to more mobile toddlers and that they can easily get out of their way. And while some cats may alert their owners when the baby starts to fuss and cry, others will disappear until someone tends to the baby’s needs and things quiet down again.

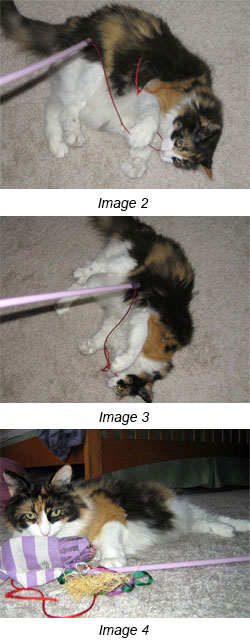

The second reason it can be difficult to bite- and scratch-proof some youngsters has to do with the way we play with cats. If you observe many human-feline games, you can see how often these generate the stalk, pounce, pinion, or bite steps of the predatory sequence. (Images 2-4) This is not to say that people shouldn’t play those kinds of games with cats when there are youngsters in the household, but rather that they should use some common sense when doing so.

For high energy cats who get really riled up during play, limit play sessions to when the child is napping or down for the night. When playing stalk and pounce games, always make sure to end the game with the cat capturing the toy/prey. Don’t stimulate a cat up to the pounce or bite phase with a toy, then abort the game because the phone rings or the baby awakens. Even though you may have what you consider far more important things to do, you’ve primed that cat to pounce on or bite something (or someone). Give the cat an appropriate target rather than hoping the cat finds one herself.

Along those same lines, I’m not a big fan of laser penlight play with cats because it can lead to obsessive compulsive displays in stressed animals. In these cases, the cats may become shadow chasers, trying to unsuccessfully pinion and bite sunbeams or shadows. This is not a good thing when that play of light and shadow may occur where the baby or toddler is napping, playing, or eating. If you’re already playing such games and not experiencing any problems, just make sure you end the game by shining the light on a toy that the cat can catch for real. If your cat shows evidence of compulsive shadow- or light-chasing, gradually phase out the game in favor of one that uses tangible targets for the cat’s energy. If you’ve never played such games with your cat, there’s no reason to start now.

Like healthy, well-behaved dogs, healthy, well-behaved cats can add a marvelous dimension to children’s lives. All that’s necessary is for adults to recognize what makes cats so special and meet those needs in a way that guarantees the health and safety of any youngsters, too.

If you have any comments regarding subject matter, favorite links, or anything you’d like to see discussed on or added to this site, please let me know at mm@mmilani.com.

The good news about cats is that their more solitary nature leads many to view infants and young children as offspring rather than engage in competitive relationships with them. If the cat has the confidence to handle this, he or she may become a self-appointed mom’s or dad’s little helper, carefully observing the baby’s nursing/feeding, bathing, and diaper-changing rituals to ensure it’s done properly. These cats also may periodically check on the sleeping infant just like any concerned parent.

Some cats who adopt this approach will even attempt to teach the child to hunt, a routine that’s not uncommon when a new puppy is added to a household that already includes a hunting cat, and especially a female. A friend tells the story of how he and his wife brought home their first newborn and lovingly placed her in her brand new crib in their perfectly decorated nursery. After making sure she was sleeping, they slipped away to the kitchen to get something to eat. When they returned, they found a dead mouse carefully positioned beside the sleeping infant and the cat curled up sound asleep at the opposite end of the crib.

Fortunately both parents knew enough about feline behavior that they were not so horrified by this feline act that they immediately carted the cat off to the veterinarian’s to be euthanized for disgusting or dangerous behavior. Instead, they saw the behavior for what it was: the cat’s attempt to feed her young. As my friend noted when he recounted the tale to me later, “Who knows? Maybe the cat was appalled that we went off and fed ourselves and left the baby there alone and with nothing to eat.”

There are many such stories of feline devotion and I’ve had similar experiences with my own cats and kids as infants, the memories of which I cherish. However, it would be naive to believe that all cats are like this. Similarly, it would be as misguided to believe there was something wrong with a cat who chose to have minimal contact with an infant or child as it would be to believe likewise about one of those furry nannies.

The not-so-good news about cats for some parents is that cats are, at heart, cats. And that means that they are members of a nonverbal species that communicates with their teeth and claws. Like dogs, how much force they put behind their jaws depends on how much stimulation they get from their targets or the environment. When a queen (mother cat) picks up her kitten by the scruff of the neck, the kitten instinctively knows to remain silent with limbs curled close to the body. Not only does this make it easier for the queen to transport her young, it prevents predators from being alerted by any kittenish thrashing or noises during this vulnerable period. While the queen does hold her kittens with her teeth, they’re unharmed because she applies just enough pressure to get the job done.

When the job the adult cat wants done is offing a rodent or confronting a predator, that’s a whole different ball game. In that case, the stimulus the cat receives from the other triggers a far more powerful bite. Similarly, gentle playful and disciplinary batting with paws can give way to slashes with unsheathed claws when stimulus reaches a certain level.

Theoretically, the solution to this potential problem is simple: don’t stimulate the cat in a manner that increases the likelihood that the animal will bite or unsheath those claws. However, that’s one of those things that’s often a lot easier to say than actually do for two reasons.

The first is that young children can be both noisy and unpredictable. Unless adults have taught the child to be quiet, gentle, and respectful around animals, the potential exists for a cat who merely intended to hold the little poking and prodding child’s finger to clamp on if the child squeals in surprise or even delight. If parents or other caregivers panic and rush or yell at the cat, that could produce the same unfortunate result. If those folks roughly grab the cat and yank the animal away from the child, they shouldn’t be surprise if the cat’s claws come out and dig in at the same time as those fangs dig in deeper, turning that small puncture wound into a deep laceration.

What about infants who may spend a fair amount of their waking hours crying and flailing about? With rare exceptions, cats seem to recognize that infants pose little threat compared to more mobile toddlers and that they can easily get out of their way. And while some cats may alert their owners when the baby starts to fuss and cry, others will disappear until someone tends to the baby’s needs and things quiet down again.

The second reason it can be difficult to bite- and scratch-proof some youngsters has to do with the way we play with cats. If you observe many human-feline games, you can see how often these generate the stalk, pounce, pinion, or bite steps of the predatory sequence. (Images 2-4) This is not to say that people shouldn’t play those kinds of games with cats when there are youngsters in the household, but rather that they should use some common sense when doing so.

For high energy cats who get really riled up during play, limit play sessions to when the child is napping or down for the night. When playing stalk and pounce games, always make sure to end the game with the cat capturing the toy/prey. Don’t stimulate a cat up to the pounce or bite phase with a toy, then abort the game because the phone rings or the baby awakens. Even though you may have what you consider far more important things to do, you’ve primed that cat to pounce on or bite something (or someone). Give the cat an appropriate target rather than hoping the cat finds one herself.

Along those same lines, I’m not a big fan of laser penlight play with cats because it can lead to obsessive compulsive displays in stressed animals. In these cases, the cats may become shadow chasers, trying to unsuccessfully pinion and bite sunbeams or shadows. This is not a good thing when that play of light and shadow may occur where the baby or toddler is napping, playing, or eating. If you’re already playing such games and not experiencing any problems, just make sure you end the game by shining the light on a toy that the cat can catch for real. If your cat shows evidence of compulsive shadow- or light-chasing, gradually phase out the game in favor of one that uses tangible targets for the cat’s energy. If you’ve never played such games with your cat, there’s no reason to start now.

Like healthy, well-behaved dogs, healthy, well-behaved cats can add a marvelous dimension to children’s lives. All that’s necessary is for adults to recognize what makes cats so special and meet those needs in a way that guarantees the health and safety of any youngsters, too.

If you have any comments regarding subject matter, favorite links, or anything you’d like to see discussed on or added to this site, please let me know at mm@mmilani.com.