When a dog bites a person’s face, it’s not uncommon for someone to attribute the wounds to the dog’s predatory nature. However, these bites rarely represent predatory responses. More often than not, these dogs are playing by dog- rather than human rules, thanks to the animal’s relationship with humans. And dogs playing by dog rules naturally communicate in the way they communicate with other dogs: they use their teeth. Unfortunately when they communicate this way to young children and infants, the youngsters often get bitten on the face.

“Who cares why the dog bites?” you may ask. Well, I do for one because understanding what is going on will help parents protect themselves and their families from such injuries. And given the number of dogs who are euthanized for biting kids this way, this knowledge could save some dog lives, too.

Before reading on, open your dog’s mouth and examine your pet’s teeth. (If you can’t do this, i.e. your dog won’t allow you to do this, get some professional behavioral/bond help because this could be an indicator of more serious problems.) When most people look at a dog’s teeth, the first thing they notice are those four canine teeth or fangs. Although we often think of them as potential dental weapons of mass destruction, they also serve another, kinder gentler function.

Look at this drawing of a canine skull. (Image 1) Notice how the tips of the fangs extend above or below the level of the premolars and molars behind them. This enables a dog to grab and hold another dog by applying four small points of pressure, thereby protecting the other from the crushing force of the premolars and molars. Additionally, when dogs want to communicate with other dogs, they grab them in two very specific places: by the muzzle or on the head behind the ears. So if, for example, a pup wants to communicate to a littermate that he’s superior (Image 2), he makes this point by grabbing the littermate’s muzzle. Similarly, adults who want to communicate to overly rambunctious pups that their behavior is rude and unacceptable will do the same thing. (Image 3)

Look at this drawing of a canine skull. (Image 1) Notice how the tips of the fangs extend above or below the level of the premolars and molars behind them. This enables a dog to grab and hold another dog by applying four small points of pressure, thereby protecting the other from the crushing force of the premolars and molars. Additionally, when dogs want to communicate with other dogs, they grab them in two very specific places: by the muzzle or on the head behind the ears. So if, for example, a pup wants to communicate to a littermate that he’s superior (Image 2), he makes this point by grabbing the littermate’s muzzle. Similarly, adults who want to communicate to overly rambunctious pups that their behavior is rude and unacceptable will do the same thing. (Image 3)

Meanwhile, dogs who are playing with other dogs will also try to grab each other this way. (Image 4) However, in this case, they’ve made their playful intent clear before-the-fact.

Meanwhile, dogs who are playing with other dogs will also try to grab each other this way. (Image 4) However, in this case, they’ve made their playful intent clear before-the-fact.

For as horrific as this grabbing with teeth appears, dogs often use their teeth the way we use our hands. Who hasn’t seen a child using his hands to grab and/or pin a sibling to force the latter to give up a toy or secret, or an adult grabbing and holding an out-of-control child to calm her, or kids grabbing and pinning each other in make-believe games of cops and robbers or earthlings and aliens?

Additionally, this form of canine communication also has an exquisite method behind it. One reason dogs often grab each other by the muzzle is because there’s little in that area but skin and bone. When most dogs feel that bone, their first instinct is to stop. If the target makes the proper response, i.e., submits/freezes, little physical damage is done. On the other hand, if the target resists, then the initiator will apply more pressure. The more deeply the fangs dig in, the closer those premolars and molars come to the skin. (Compare this to a predatory attack in which predators target the soft tissue around the neck where they can do a maximum amount of fatal damage using a minimal amount of energy.)

In addition to the dog sending the message—”Give that toy back, it’s mine.” “Stop acting like a jerk, Junior.” “What a game!”—in a way designed to prevent serious injury, the canine recipient also knows the proper response in those particular circumstances.

Unfortunately, because many humans do not understand how, let alone what, their dogs are communicating, they don’t know the proper response. So instead of freezing, they scream, wave their hands, and carry on.

As you consider basic canine jaw anatomy and look at these pictures of normal canine displays that evolved to enable dogs to communicate with their teeth without harming each other, I’m sure you can figure out how kids (and adults who unwisely get in dogs’ faces) can incur injuries that leave physical and psychological scars that may take years to heal.

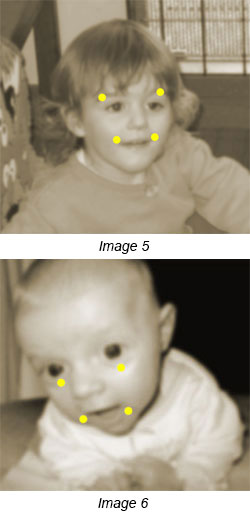

Painful though it may be for you parents-to-be, parents, or grandparents, consider these pictures of a 3-year-old and an infant. (Images 5 and 6) Perhaps they’re eying a colorful ball (their own or the dog’s) next to the animal, or maybe just establishing eye contact with the dog. If the dog views the child or baby as a subordinate and lacks confidence to deal with all the responsibilities inherent in that, then he may consider these, to us, innocent displays as evidence of gross insubordination. Because adults in the household haven’t communicated to the dog that he or she lives in a human world and is expected to play by human rules, the unconfident leader dog grabs the child by the “muzzle” with those fangs to communicate his/her higher rank. The size of the dog determines where those initial points of contact will be, but the yellow circles on the pictures show possible positioning.

Painful though it may be for you parents-to-be, parents, or grandparents, consider these pictures of a 3-year-old and an infant. (Images 5 and 6) Perhaps they’re eying a colorful ball (their own or the dog’s) next to the animal, or maybe just establishing eye contact with the dog. If the dog views the child or baby as a subordinate and lacks confidence to deal with all the responsibilities inherent in that, then he may consider these, to us, innocent displays as evidence of gross insubordination. Because adults in the household haven’t communicated to the dog that he or she lives in a human world and is expected to play by human rules, the unconfident leader dog grabs the child by the “muzzle” with those fangs to communicate his/her higher rank. The size of the dog determines where those initial points of contact will be, but the yellow circles on the pictures show possible positioning.

What can make such injuries so devastating is that we humans don’t have protective muzzles, so the probability that the dog would grab something other than bone and inhibit the bite/hold is less. However, if the child is fortunate, two things will happen. The first is that the child will instinctively freeze, and the second is that no one else in the vicinity will start screaming or otherwise feeding stimuli into the process. In that case, the dog will let go and the child will have bruises (or less) at the points of contact. On the other hand, if the child or others react and try to pull the child away, the dog will not only apply more pressure but any motion away from the dog will result in lacerations and other more serious damage.

Ironically this leads to a tragic paradox. No one in their right mind would suggest that a dog ever be left with an infant or young child without adult supervision. On the other hand, kids who are alone when a dog grabs them may fare better because they’re more likely to instinctively freeze whereas their caregivers are more apt to panic.

Needless to say, when children sustain such injuries the most common response is to euthanize the dog. It also goes without saying that no one, and especially no parent whose child has been bitten, would even consider giving up an aggressive animal to a shelter or rescue group unless they were positive that a) the animal’s problem would be successfully treated before the animal was re-homed, or b) the animal would be put down. The reason for this is obvious: unless something is done to resolve the underlying cause of the dog’s behavior, he or she will bite again. Nor am I going to suggest that parents keep dogs they do not trust and can’t imagine ever trusting again.

That said, I will also add that these animals can be treated, but it does take a lot of time and commitment. However, that primary prerequisite of all successful behavioral-bond changes—consistency—is often difficult to achieve in a household with an infant or young children. Add the fact that the dog must be kept away from those children until human leadership replaces canine and that the adults in the household often must change as much if not more than the dog, and the process is not for the faint of heart or those short of time and energy.

Because of this and speaking yet again as a former mother and current doting grandmother, I would urge all parents-to-be and new parents to get their canine as well as human households in order before problems arise. For those who have experienced problems and given up a dog as a result, don’t delude yourself that there was something wrong with the dog, that he or she was somehow the exception to the rule, or even that the bite “came out of the blue.” With rare exceptions and regardless of the underlying cause, the overwhelming majority of biting dogs give their owners plenty of warning before that first what we consider inappropriate bite occurs. It’s just that the emotion- rather than knowledge-based meanings we as individuals and a society assign to those displays often lead us to dismiss or ignore them.

When a dog bites a person’s face, it’s not uncommon for someone to attribute the wounds to the dog’s predatory nature. However, these bites rarely represent predatory responses. More often than not, these dogs are playing by dog- rather than human rules, thanks to the animal’s relationship with humans. And dogs playing by dog rules naturally communicate in the way they communicate with other dogs: they use their teeth. Unfortunately when they communicate this way to young children and infants, the youngsters often get bitten on the face.

“Who cares why the dog bites?” you may ask. Well, I do for one because understanding what is going on will help parents protect themselves and their families from such injuries. And given the number of dogs who are euthanized for biting kids this way, this knowledge could save some dog lives, too.

Before reading on, open your dog’s mouth and examine your pet’s teeth. (If you can’t do this, i.e. your dog won’t allow you to do this, get some professional behavioral/bond help because this could be an indicator of more serious problems.) When most people look at a dog’s teeth, the first thing they notice are those four canine teeth or fangs. Although we often think of them as potential dental weapons of mass destruction, they also serve another, kinder gentler function.

For as horrific as this grabbing with teeth appears, dogs often use their teeth the way we use our hands. Who hasn’t seen a child using his hands to grab and/or pin a sibling to force the latter to give up a toy or secret, or an adult grabbing and holding an out-of-control child to calm her, or kids grabbing and pinning each other in make-believe games of cops and robbers or earthlings and aliens?

Additionally, this form of canine communication also has an exquisite method behind it. One reason dogs often grab each other by the muzzle is because there’s little in that area but skin and bone. When most dogs feel that bone, their first instinct is to stop. If the target makes the proper response, i.e., submits/freezes, little physical damage is done. On the other hand, if the target resists, then the initiator will apply more pressure. The more deeply the fangs dig in, the closer those premolars and molars come to the skin. (Compare this to a predatory attack in which predators target the soft tissue around the neck where they can do a maximum amount of fatal damage using a minimal amount of energy.)

In addition to the dog sending the message—”Give that toy back, it’s mine.” “Stop acting like a jerk, Junior.” “What a game!”—in a way designed to prevent serious injury, the canine recipient also knows the proper response in those particular circumstances.

Unfortunately, because many humans do not understand how, let alone what, their dogs are communicating, they don’t know the proper response. So instead of freezing, they scream, wave their hands, and carry on.

As you consider basic canine jaw anatomy and look at these pictures of normal canine displays that evolved to enable dogs to communicate with their teeth without harming each other, I’m sure you can figure out how kids (and adults who unwisely get in dogs’ faces) can incur injuries that leave physical and psychological scars that may take years to heal.

What can make such injuries so devastating is that we humans don’t have protective muzzles, so the probability that the dog would grab something other than bone and inhibit the bite/hold is less. However, if the child is fortunate, two things will happen. The first is that the child will instinctively freeze, and the second is that no one else in the vicinity will start screaming or otherwise feeding stimuli into the process. In that case, the dog will let go and the child will have bruises (or less) at the points of contact. On the other hand, if the child or others react and try to pull the child away, the dog will not only apply more pressure but any motion away from the dog will result in lacerations and other more serious damage.

Ironically this leads to a tragic paradox. No one in their right mind would suggest that a dog ever be left with an infant or young child without adult supervision. On the other hand, kids who are alone when a dog grabs them may fare better because they’re more likely to instinctively freeze whereas their caregivers are more apt to panic.

Needless to say, when children sustain such injuries the most common response is to euthanize the dog. It also goes without saying that no one, and especially no parent whose child has been bitten, would even consider giving up an aggressive animal to a shelter or rescue group unless they were positive that a) the animal’s problem would be successfully treated before the animal was re-homed, or b) the animal would be put down. The reason for this is obvious: unless something is done to resolve the underlying cause of the dog’s behavior, he or she will bite again. Nor am I going to suggest that parents keep dogs they do not trust and can’t imagine ever trusting again.

That said, I will also add that these animals can be treated, but it does take a lot of time and commitment. However, that primary prerequisite of all successful behavioral-bond changes—consistency—is often difficult to achieve in a household with an infant or young children. Add the fact that the dog must be kept away from those children until human leadership replaces canine and that the adults in the household often must change as much if not more than the dog, and the process is not for the faint of heart or those short of time and energy.

Because of this and speaking yet again as a former mother and current doting grandmother, I would urge all parents-to-be and new parents to get their canine as well as human households in order before problems arise. For those who have experienced problems and given up a dog as a result, don’t delude yourself that there was something wrong with the dog, that he or she was somehow the exception to the rule, or even that the bite “came out of the blue.” With rare exceptions and regardless of the underlying cause, the overwhelming majority of biting dogs give their owners plenty of warning before that first what we consider inappropriate bite occurs. It’s just that the emotion- rather than knowledge-based meanings we as individuals and a society assign to those displays often lead us to dismiss or ignore them.