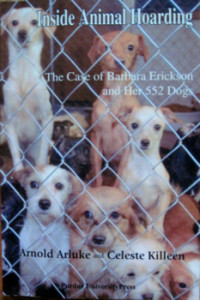

I’d written a review of another mass media bond-book and had fully intended to post it this month when I received a copy of Inside Animal Hoarding: The Case of Barbara Erickson and Her 552 Dogs by Arnold Arluke and Celeste Killeen (Purdue University Press, 2009).For me, the subject matter was so pertinent and well-presented it seemed to me that every self-proclaimed animal-lover, everyone involved in shelter or rescue work in any capacity, every veterinarian, vet tech, behaviorist, and trainer, and indeed anyone engaged in animal-related activities of any kind should read this book.

I’d written a review of another mass media bond-book and had fully intended to post it this month when I received a copy of Inside Animal Hoarding: The Case of Barbara Erickson and Her 552 Dogs by Arnold Arluke and Celeste Killeen (Purdue University Press, 2009).For me, the subject matter was so pertinent and well-presented it seemed to me that every self-proclaimed animal-lover, everyone involved in shelter or rescue work in any capacity, every veterinarian, vet tech, behaviorist, and trainer, and indeed anyone engaged in animal-related activities of any kind should read this book.

But why? What makes this book so different from all the other bond-related books out there?

The most obvious—and refreshing—difference is the form. In a previous book review I wrote about the shift in publishing from books written from the inside, i.e., by those with firsthand knowledge of a subject, to those written from the outside, i.e. by professional journalists. Inside Animal Hoarding: The Case of Barbara Erickson and Her 552 Dogs provides readers with a rare opportunity to compare and contrast these different ways of addressing the same subject and to learn from both.

The book is divided into two parts. In the first part, journalist Celeste Killeen describes her efforts to understand how someone who claimed to love dogs so much wound up keeping so many under such deplorable conditions. What intrigued Killeen from the first day she saw and heard the news reports describing the dramatic removal of the dogs from their wretched surroundings was that, in spite of all the opinions offered by experts—law enforcement officers, veterinarians, shelter workers—apparently none of them had actually talked to Barbara Erickson. How could she or anyone could hope to understand what compelled this pathetic old woman to keep more animals than she and her husband could possibly care for properly based on such secondhand opinions? Unlike a lot of people who were intimately or tangentially involved in the case, Celeste Killeen was more interested in why it happened than the consequences. And because I’m a firm believer that the only chance we have to prevent or eliminate any negative behavior is to understand why it happened in the first place, I quickly became immersed in her narrative.

Instead of interviewing Ms Erickson using a list of questions that reflected what was import to her as a journalist, Killeen listened to Erickson, which was not always an easy task. And rather than perceiving the obviously false claims the woman made as evidence that she was mentally deranged and therefore nothing she said had merit, Killeen recorded their conversations and took copious notes. Then she interviewed those who had known Barbara Erickson, her husband and others who interacted with the couple and/or the case, made more notes, and asked more questions. And like all good reporters, she checked any facts using multiple sources.

After she did all that, Killeen pieced together a narrative of events based on what she learned during this process. Unlike some journalistic offerings, she does not present her version as the truth. Quite the contrary. She fully acknowledges from her own response to the event that hoarding is a subject that elicits strong emotions. And as most of us know, there’s no shortage of people who erroneously equate the strength of their emotions and the personal opinions that accompany these with truth. Fortunately for the reader, Killeen is not one of them.

Had the book ended there, it would have joined that increasing population of books written by journalists that presume to represent the truth or to which naive readers assign that power. But Inside Animal Hoarding does not follow that possibly more entertaining but, to me, ultimately more frustrating and irritating path. Instead in Part Two of the book Arnold Arluke, Professor of Sociology and Anthropology at Northeastern University and author of many books and articles on human-animal interactions, discusses the case of Barbara Erickson and her 552 dogs in terms of what is actually known about hoarding.

Arluke begins by providing an overview of hoarders that, like closer examination of most animal-related phenomena, reveals some similarities to the common stereotype but challenges some aspects of it, too. For example, there are different kinds of hoarders and different degrees of hoarding within them. The thought that some rescuers fall into this category may not be surprising to some, but may be quite disconcerting to others.

Using news reports, Arluke then describes how the media perpetuates the long-standing view of hoarding as eccentric behavior. How this is defined and what emotional spin is put on it may be more of a function of human bias than objective reporting, with hoarders portrayed as cruel, “loving too much,” and everything between. Opinions of humane society and other animal-care professionals as well as members of the law enforcement community regarding what motivates a hoarder were also presented in the media as if these were based on known facts. Given the endless repetition of such reports, it’s no wonder that the public comes to accept these opinions as true.

The reality is that we know precious little about what causes some people to amass large numbers of animals. In fact, after reading Arluke’s discussion of possible theories and contributing factors, it strikes me that while hoarding is often viewed in terms of numbers, it’s more a question of that person’s fundamental view of animals. That is, it might be possible for us to be hoarders of a socially acceptable number of pets if the symbolic meaning we placed on those animals blocked our ability to see them as beings of a different species with their own unique physical and behavioral needs that it was our responsibility to fulfill. In that case, it would be the willingness to cling to any belief about them and/or our relationship to them that blinds us to their needs that would be the real problem.

Arluke closes with discussion of why animal hoarding cases so fascinate us, turning once again to the role the media plays in this and our views of hoarding. His analysis of what journalists emphasize in these cases probably will surprise many. Those who have read or watched such reports may have realized just how biased these accounts are just as I did. Pondering this was a real eye-opener for me and led to some much more personal and deeper thoughts—which Arluke points out could be another reason why these reports so intrigue us. True, it could be that we’re drawn to descriptions of hoarders because these people are so alien to our own beliefs about the humans and animals with whom we live in our communities. But it could also be that we’re attracted to them because, on some level, we all acknowledge that we’re more alike than different.

But why? What makes this book so different from all the other bond-related books out there?

The most obvious—and refreshing—difference is the form. In a previous book review I wrote about the shift in publishing from books written from the inside, i.e., by those with firsthand knowledge of a subject, to those written from the outside, i.e. by professional journalists. Inside Animal Hoarding: The Case of Barbara Erickson and Her 552 Dogs provides readers with a rare opportunity to compare and contrast these different ways of addressing the same subject and to learn from both.

The book is divided into two parts. In the first part, journalist Celeste Killeen describes her efforts to understand how someone who claimed to love dogs so much wound up keeping so many under such deplorable conditions. What intrigued Killeen from the first day she saw and heard the news reports describing the dramatic removal of the dogs from their wretched surroundings was that, in spite of all the opinions offered by experts—law enforcement officers, veterinarians, shelter workers—apparently none of them had actually talked to Barbara Erickson. How could she or anyone could hope to understand what compelled this pathetic old woman to keep more animals than she and her husband could possibly care for properly based on such secondhand opinions? Unlike a lot of people who were intimately or tangentially involved in the case, Celeste Killeen was more interested in why it happened than the consequences. And because I’m a firm believer that the only chance we have to prevent or eliminate any negative behavior is to understand why it happened in the first place, I quickly became immersed in her narrative.

Instead of interviewing Ms Erickson using a list of questions that reflected what was import to her as a journalist, Killeen listened to Erickson, which was not always an easy task. And rather than perceiving the obviously false claims the woman made as evidence that she was mentally deranged and therefore nothing she said had merit, Killeen recorded their conversations and took copious notes. Then she interviewed those who had known Barbara Erickson, her husband and others who interacted with the couple and/or the case, made more notes, and asked more questions. And like all good reporters, she checked any facts using multiple sources.

After she did all that, Killeen pieced together a narrative of events based on what she learned during this process. Unlike some journalistic offerings, she does not present her version as the truth. Quite the contrary. She fully acknowledges from her own response to the event that hoarding is a subject that elicits strong emotions. And as most of us know, there’s no shortage of people who erroneously equate the strength of their emotions and the personal opinions that accompany these with truth. Fortunately for the reader, Killeen is not one of them.

Had the book ended there, it would have joined that increasing population of books written by journalists that presume to represent the truth or to which naive readers assign that power. But Inside Animal Hoarding does not follow that possibly more entertaining but, to me, ultimately more frustrating and irritating path. Instead in Part Two of the book Arnold Arluke, Professor of Sociology and Anthropology at Northeastern University and author of many books and articles on human-animal interactions, discusses the case of Barbara Erickson and her 552 dogs in terms of what is actually known about hoarding.

Arluke begins by providing an overview of hoarders that, like closer examination of most animal-related phenomena, reveals some similarities to the common stereotype but challenges some aspects of it, too. For example, there are different kinds of hoarders and different degrees of hoarding within them. The thought that some rescuers fall into this category may not be surprising to some, but may be quite disconcerting to others.

Using news reports, Arluke then describes how the media perpetuates the long-standing view of hoarding as eccentric behavior. How this is defined and what emotional spin is put on it may be more of a function of human bias than objective reporting, with hoarders portrayed as cruel, “loving too much,” and everything between. Opinions of humane society and other animal-care professionals as well as members of the law enforcement community regarding what motivates a hoarder were also presented in the media as if these were based on known facts. Given the endless repetition of such reports, it’s no wonder that the public comes to accept these opinions as true.

The reality is that we know precious little about what causes some people to amass large numbers of animals. In fact, after reading Arluke’s discussion of possible theories and contributing factors, it strikes me that while hoarding is often viewed in terms of numbers, it’s more a question of that person’s fundamental view of animals. That is, it might be possible for us to be hoarders of a socially acceptable number of pets if the symbolic meaning we placed on those animals blocked our ability to see them as beings of a different species with their own unique physical and behavioral needs that it was our responsibility to fulfill. In that case, it would be the willingness to cling to any belief about them and/or our relationship to them that blinds us to their needs that would be the real problem.

Arluke closes with discussion of why animal hoarding cases so fascinate us, turning once again to the role the media plays in this and our views of hoarding. His analysis of what journalists emphasize in these cases probably will surprise many. Those who have read or watched such reports may have realized just how biased these accounts are just as I did. Pondering this was a real eye-opener for me and led to some much more personal and deeper thoughts—which Arluke points out could be another reason why these reports so intrigue us. True, it could be that we’re drawn to descriptions of hoarders because these people are so alien to our own beliefs about the humans and animals with whom we live in our communities. But it could also be that we’re attracted to them because, on some level, we all acknowledge that we’re more alike than different.