As a young child, dying Easter eggs was a favorite annual ritual in my home. Using that mysterious mathematical genius of mothers on tight budgets everywhere, Mom would determine exactly how many hard-boiled eggs the family would eat, round that number off to the nearest one that could be divided equally among 3 kids, boil the eggs, and give each of us our share to dye. While the eggs boiled, we kids covered the kitchen table with newspapers, prepared the dyes and other decorating paraphernalia, and staked out our dying stations.

Far too soon, only one egg remained in my boiled egg stash and the urge to make it the most memorable Easter egg of them all inevitably overcame me. With visions of an egg with multiple stripes of color that would blend into each other like those of a rainbow, I’d dip my egg briefly into each cup of dye and move quickly on to the next color.

But the rainbow never materialized. Because I tried to do too much too fast, each successive dunking contributed to what ultimately became a mottled brown egg.

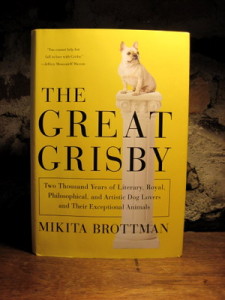

This long-forgotten memory occurred to me as I finished reading The Great Grisby by Mikita Brottman. Like my egg-dying experiences, I began the book with enthusiasm. According to its subtitle, The Great Grisby would cover two thousand years of literary, royal, philosophical and artistic dog lovers and their animals. According to the introduction, it would answer multiple questions about the human-canine bond that have engrossed anthrozoologists and others interested in the bond for decades. To accomplish this, the text would delve into the lives of twenty-six human-canine combinations often overlooked by history. Additionally the behaviors of the author’s French bulldog, Grisby, and her relationship with him would feature prominently in the book.

This long-forgotten memory occurred to me as I finished reading The Great Grisby by Mikita Brottman. Like my egg-dying experiences, I began the book with enthusiasm. According to its subtitle, The Great Grisby would cover two thousand years of literary, royal, philosophical and artistic dog lovers and their animals. According to the introduction, it would answer multiple questions about the human-canine bond that have engrossed anthrozoologists and others interested in the bond for decades. To accomplish this, the text would delve into the lives of twenty-six human-canine combinations often overlooked by history. Additionally the behaviors of the author’s French bulldog, Grisby, and her relationship with him would feature prominently in the book.

How could a book that focused on the three primary areas of academic and clinical interest for my entire career be anything less than perfect? I looked forward to learning about more obscure dogs with intriguing names such as Atma, Quinine, and Xolotl, and the people with whom they shared their lives. I eagerly anticipated new answers to those complex bond questions, as well as discovering more about the specific relationship and bond between the author and her dog.

Unfortunately in my enthusiasm, I forgot to keep the crucial last paragraph of the introduction in mind. It informs readers that the book’s structure mimics a leisurely stroll in the park with an off-lead Grisby: it isn’t always direct, it gets side-tracked, it backtracks. For example while Chapter One (Atma) provides a comprehensive discussion about dog names from a historical perspective and about how Grisby came to be called Grisby, Chapter Two (Bull’s-eye) begins with a discussion of dogs as human alter-egos then moves on to one about Grisby’s training or lack thereof, dog-fighting, and the author’s fears that someone might steal her dog. Chapter Three, Caesar III, begins with a discussion of Willa Cather’s short story “Coming, Aphrodite!” about a common bond phenomenon: the problems that arise between couples when their incompatible perceptions of a dog belonging to one of them lead to conflict. This leads to a discussion of a fiction dog in Edith Wharton’s House of Mirth, followed by those about Wharton’s real dogs, taking dogs on trains, Amtrak’s no-pet policy, and walking and riding with Grisby.

That’s tough going for someone like me whose background in the biological sciences and clinical veterinary medical and ethological practice required the development of an organized—some might say anal—mind!

But while I readily admit I may be more impaired than others in this regard, I do think that a bit more organization and a bit less wandering would have benefited a book that attempts to cover as much ground as The Great Grisby does. Answering all the human-canine bond questions the author proposed to answer is a monumental enough task without being restricted to using obscure canine examples whose names begin with specific letters of the alphabet.

That each chapter of The Great Grisby bears the name of a specific dog also raises expectations that the dog will feature prominently in the material. But while each chapter does begin with a discussion of the dog, how much presumably depends on how much actually is known about the obscure dog as this relates to the topics considered in the second part of the chapter.

The second chapter component takes one or more aspects of the title dog and his/her relationship with the owner or other humans and then expands it to make some point about the human-canine relationship in general. This component of each relatively short chapter may contain multiple references to people and their dogs, and their and their friends’ and society’s responses to their dogs, as well as references to similar human-canine interactions in other times and places. Plus references to related works of fiction and nonfiction as well as paintings and music.

Because introducing readers to more obscure dogs and dog-related references is the goal of this part of each chapter, an impressive amount of research often underlies these. But while I usually can keep unfamiliar names straight given sufficient context, the multitude of unfamiliar canine, human and other names in some of The Great Grisby’s short chapters often overwhelmed me. On multiple occasions I became so engrossed in trying to keep everyone and all the references straight that I came to the end of the chapter with no appreciation of any unifying theme.

For more organized—or anal if you prefer—readers such as yours truly, fewer more fully developed examples would have made the text more memorable. Similarly, descriptive chapter subtitles or a short opening paragraph that described the purpose of each chapter and if and how it relates to the overall theme of the book would have helped. Barring that, an index at the end of the book that would enable readers to locate topics of interest would have been appreciated.

The third element in each of The Great Grisby’s chapters comprises an abbreviated dogoir. More specifically it’s a subset of that genre, a first-dog dogoir. For those unfamiliar with the word, a dogoir is a memoir via which authors deliberately or unwittingly use their dogs and their relationships with those animals as a vehicle for exploring themselves. Relative to the human-animal bond this component of the book is the most intimate, accessible, and revealing. Unlike the other people in the book whose specific projections of emotions, beliefs, or symbolism on their animals may warrant a few pages at most, those involving the author and Grisby wander through the entire book like an off-lead untrained dog in a crowded park.

Even so, I wanted to know more this first dog-owner and her first dog, a desire that began on the third page when the author wrote: As of the time of writing, Grisby is almost eight years old, and he tips the scales at thirty-two pounds. There it was, possible evidence of perhaps the most perplexing bond-related problem currently plaguing companion dogdom: pet dog overweight and obesity. Standard weight range for purebred French Bulldogs is 18-28 pounds. Would the author use her considerable historical research and introspective skills to explore the role of the human-animal bond in canine overweight and obesity? Historically was overfeeding dogs in certain cultures considered a way to communicate one’s wealth and position to others? Or one’s love to one’s animal because words inadequate? Or an individual or societal belief that no gift of self could measure up to a piece of cake or dish of pudding?

Aside from the author expressing anger when a veterinarian comments on Grisby’s excess weight, the subject receives little attention. While initially disappointed, in the end I decided this was probably was rightly so. Overweight and obesity rank high among those with an interest in contemporary canine health and behavior. But neither is obscure, even though the bond’s role in both often does get dismissed or ignored completely. On the other hand, The Great Grisby is a book about the past as experienced by little known dogs as perceived by a formidable array of historical personages from an equally formidable array of backgrounds. The Grisby component provides an integral contrast, an intimate vignette of a contemporary first-dog owner doing what most of us in that position do or did: naively try to come up with the right combination of interactions and projection of emotions, symbolism, and beliefs that will result in what we consider the best bond experience for us. In that regard, the book succeeds very well.

As a young child, dying Easter eggs was a favorite annual ritual in my home. Using that mysterious mathematical genius of mothers on tight budgets everywhere, Mom would determine exactly how many hard-boiled eggs the family would eat, round that number off to the nearest one that could be divided equally among 3 kids, boil the eggs, and give each of us our share to dye. While the eggs boiled, we kids covered the kitchen table with newspapers, prepared the dyes and other decorating paraphernalia, and staked out our dying stations.

Far too soon, only one egg remained in my boiled egg stash and the urge to make it the most memorable Easter egg of them all inevitably overcame me. With visions of an egg with multiple stripes of color that would blend into each other like those of a rainbow, I’d dip my egg briefly into each cup of dye and move quickly on to the next color.

But the rainbow never materialized. Because I tried to do too much too fast, each successive dunking contributed to what ultimately became a mottled brown egg.

How could a book that focused on the three primary areas of academic and clinical interest for my entire career be anything less than perfect? I looked forward to learning about more obscure dogs with intriguing names such as Atma, Quinine, and Xolotl, and the people with whom they shared their lives. I eagerly anticipated new answers to those complex bond questions, as well as discovering more about the specific relationship and bond between the author and her dog.

Unfortunately in my enthusiasm, I forgot to keep the crucial last paragraph of the introduction in mind. It informs readers that the book’s structure mimics a leisurely stroll in the park with an off-lead Grisby: it isn’t always direct, it gets side-tracked, it backtracks. For example while Chapter One (Atma) provides a comprehensive discussion about dog names from a historical perspective and about how Grisby came to be called Grisby, Chapter Two (Bull’s-eye) begins with a discussion of dogs as human alter-egos then moves on to one about Grisby’s training or lack thereof, dog-fighting, and the author’s fears that someone might steal her dog. Chapter Three, Caesar III, begins with a discussion of Willa Cather’s short story “Coming, Aphrodite!” about a common bond phenomenon: the problems that arise between couples when their incompatible perceptions of a dog belonging to one of them lead to conflict. This leads to a discussion of a fiction dog in Edith Wharton’s House of Mirth, followed by those about Wharton’s real dogs, taking dogs on trains, Amtrak’s no-pet policy, and walking and riding with Grisby.

That’s tough going for someone like me whose background in the biological sciences and clinical veterinary medical and ethological practice required the development of an organized—some might say anal—mind!

But while I readily admit I may be more impaired than others in this regard, I do think that a bit more organization and a bit less wandering would have benefited a book that attempts to cover as much ground as The Great Grisby does. Answering all the human-canine bond questions the author proposed to answer is a monumental enough task without being restricted to using obscure canine examples whose names begin with specific letters of the alphabet.

That each chapter of The Great Grisby bears the name of a specific dog also raises expectations that the dog will feature prominently in the material. But while each chapter does begin with a discussion of the dog, how much presumably depends on how much actually is known about the obscure dog as this relates to the topics considered in the second part of the chapter.

The second chapter component takes one or more aspects of the title dog and his/her relationship with the owner or other humans and then expands it to make some point about the human-canine relationship in general. This component of each relatively short chapter may contain multiple references to people and their dogs, and their and their friends’ and society’s responses to their dogs, as well as references to similar human-canine interactions in other times and places. Plus references to related works of fiction and nonfiction as well as paintings and music.

Because introducing readers to more obscure dogs and dog-related references is the goal of this part of each chapter, an impressive amount of research often underlies these. But while I usually can keep unfamiliar names straight given sufficient context, the multitude of unfamiliar canine, human and other names in some of The Great Grisby’s short chapters often overwhelmed me. On multiple occasions I became so engrossed in trying to keep everyone and all the references straight that I came to the end of the chapter with no appreciation of any unifying theme.

For more organized—or anal if you prefer—readers such as yours truly, fewer more fully developed examples would have made the text more memorable. Similarly, descriptive chapter subtitles or a short opening paragraph that described the purpose of each chapter and if and how it relates to the overall theme of the book would have helped. Barring that, an index at the end of the book that would enable readers to locate topics of interest would have been appreciated.

The third element in each of The Great Grisby’s chapters comprises an abbreviated dogoir. More specifically it’s a subset of that genre, a first-dog dogoir. For those unfamiliar with the word, a dogoir is a memoir via which authors deliberately or unwittingly use their dogs and their relationships with those animals as a vehicle for exploring themselves. Relative to the human-animal bond this component of the book is the most intimate, accessible, and revealing. Unlike the other people in the book whose specific projections of emotions, beliefs, or symbolism on their animals may warrant a few pages at most, those involving the author and Grisby wander through the entire book like an off-lead untrained dog in a crowded park.

Even so, I wanted to know more this first dog-owner and her first dog, a desire that began on the third page when the author wrote: As of the time of writing, Grisby is almost eight years old, and he tips the scales at thirty-two pounds. There it was, possible evidence of perhaps the most perplexing bond-related problem currently plaguing companion dogdom: pet dog overweight and obesity. Standard weight range for purebred French Bulldogs is 18-28 pounds. Would the author use her considerable historical research and introspective skills to explore the role of the human-animal bond in canine overweight and obesity? Historically was overfeeding dogs in certain cultures considered a way to communicate one’s wealth and position to others? Or one’s love to one’s animal because words inadequate? Or an individual or societal belief that no gift of self could measure up to a piece of cake or dish of pudding?

Aside from the author expressing anger when a veterinarian comments on Grisby’s excess weight, the subject receives little attention. While initially disappointed, in the end I decided this was probably was rightly so. Overweight and obesity rank high among those with an interest in contemporary canine health and behavior. But neither is obscure, even though the bond’s role in both often does get dismissed or ignored completely. On the other hand, The Great Grisby is a book about the past as experienced by little known dogs as perceived by a formidable array of historical personages from an equally formidable array of backgrounds. The Grisby component provides an integral contrast, an intimate vignette of a contemporary first-dog owner doing what most of us in that position do or did: naively try to come up with the right combination of interactions and projection of emotions, symbolism, and beliefs that will result in what we consider the best bond experience for us. In that regard, the book succeeds very well.